See a preview:

elle (la photo) e lui (le cinéma)

[P]hotography and cinema are the most famous couple in the visual arts of the 1900’s, and also the most intriguing, when examined closely, and as such, nicely ignored by the two distinct theoretical fields.The set is the privileged location where their game has always taken place; a game made up of attraction and revealing, mutual involvement and anonymous exchanges, based on a twisting spiral, in which the momentary and instrumental union does not cancel the different identities, but make makes them rather unsettling… except it ignores them.

In this one-hundred-year-old story, she “photography”, a small two-dimensional, silent object in search of stillness and movement, had to pay the price of working, in order to provide fame for Him, “cinema”, an animated subject by nature, as a synthesis of millions of frames, first silent, and later with spoken sound, are projected onto bigger and bigger screens, in dark rooms, where reality enters as make-believe, and even stated as such, the theoretical complexity of it, is but merely mentioned.

In fact, cinema, considered as a material object, requires that during the working phase, the director of photography be in agreement with the film director, and here, this is referring to a professional role in charge of the shooting (and the equipment involved -lenses, lighting, etc.), developing and printing “the film”. Well-determined tasks which, only nominally, refer to the shooting phase of photographic images. In theory, however, how the photographic vision of the world may have influenced or still influences that of cinema, and vice-versa, still remains a mystery.

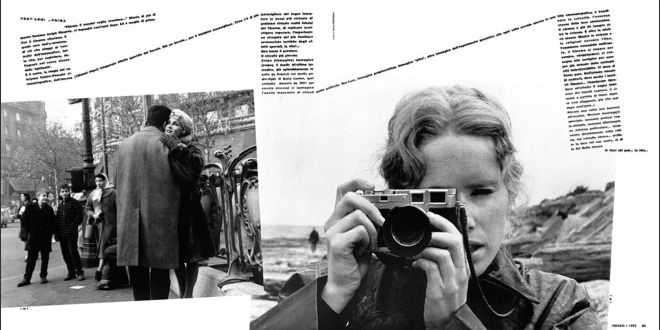

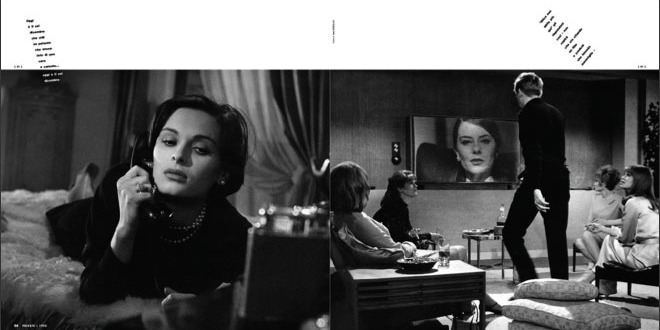

Furthermore, would this matter be simplified or complicated if we were to consider cinema as a “language”- generally speaking- with the smallest unit being the frame or an alphabetical letter of light, which when repeated in sequence, and projected at regular intervals, provides the illusion of movement? The reproduction of these images onto paper is also referred to as a frame, often used for grasping a specific fragment of the film. The points outlined here are not but a fraction of those created by the phantasmagoric relationship between Her, photography, and Him, cinema. Yes, because in order to be noticed by the great public, and in order to nourish film star legends, the cinema, or better, the industry which produces them required: – photography, such as pictures of actors and technicians at work during the shooting breaks (set photography); – Stills, taken before, during or immediately after a shooting, which are used for advertising the film; – portrait photographs, taken for the most part in the studio, in order to create legends out of beautiful and unreachable men and women, rather stars, in the early decades of the 1900’s, whose autographed photos, referred to as fan photos, thousands of fans were anxiously after.

The first two tasks were mostly up to one individual, called a set photographer, who would be called upon during a shooting, to reproduce that which the movie camera saw, into photography, taking pictures (hundreds to thousands), which gave an idea of a certain film. They re-enhance the stylistic impression – and not common recordings- and this is exactly why they were used, (as they were until the 1960’s) for play-bills, photo packages (30-40 positive prints) for the press, and photo albums, intended for selling the film abroad.

Furthermore, on the set, the photographer covers the entire work done on the film he is following, totally free to capture marginal aspects and characters, revealing their make-believe mechanisms.

If most of these shots taken eventually ended up in the personal collection of the photographer, and among these, portraits taken in the studio, it seems evident that the production of cinema photography has been, and still is rather immense, even though the number of the corresponding prints selected for distribution, results to much lower.

(by Angela Tromellini, in collaboration with the Cineteca comunale di Bologna.)